by Erin Larkin

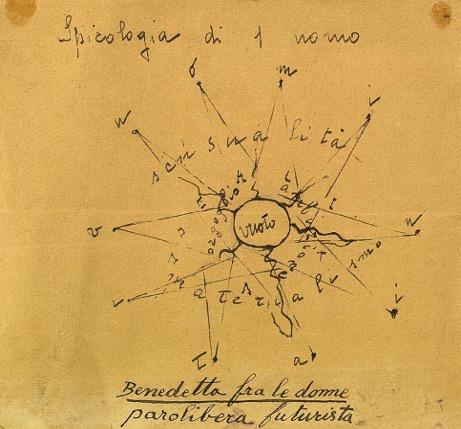

When looking for literary and cultural genealogies for Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s first female prime minister and co-founder of the ultraconservative Fratelli d’Italia, the women of Italian Futurism offer a revealing perspective. The historical avant-garde provides examples of the rhetoric of exceptionalism that continues to mark conservative feminism, particularly in the work of Benedetta Cappa. Meloni’s refrain—“Io sono Giorgia, sono una donna, sono una madre, sono italiana, sono cristiana”—reflects the same themes of nation, motherhood, and religious identity that shaped Cappa’s futurist poetics. Like Meloni, Cappa was a woman in a male-dominated movement and acknowledged the privilege of this position in her 1919 parole-in-libertà Spicologia di 1 uomo. The title plays on both futurist rejection of literary psychology and Cappa’s husband, futurist leader F.T. Marinetti. The poem’s reference to “spica,” a star in the Virgo constellation linked to ancient astrology, and its ironic Biblical citation “Benedetta fra le donne” suggest—quite ironically since Cappa was one of the few women in futurist circles—Cappa’s exploration of womanhood, motherhood, and Christianity, themes that remain central in her later works.

However, the analogy between Cappa and Meloni has limits. Cappa’s Futurism hinges on a strict masculine-feminine binary, which she never fully transcended, as seen in her 1924 novel Le Forze Umane. In contrast, Meloni plays with traditional gender roles. Her identity as a mother is a critical part of her image, with personal touches like baking cupcakes for her daughter, Ginevra. Yet, Meloni also adopts a warrior persona, embodying heroic defiance with her assertive rhetoric: “Io sono Giorgia […] e non me lo toglierete!” This blend of nurturing motherhood and combative nationalism, where Meloni positions herself as a defender of family, country, and faith, suggests that, looking for genealogies for her political performance, it would be fruitful to look to Marinetti himself.