by Diana Garvin

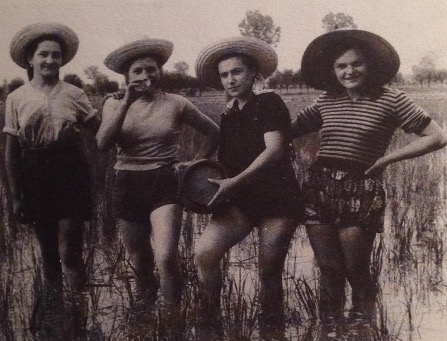

Under Mussolini’s dictatorship, both the physical abuses of a misogynist state and the political power of female friendship were written in the sensory details of agricultural workers’ everyday lives. This article uses archival and melodic evidence from the sensorial world of interwar Italy to explore four interlinked case studies, ultimately revealing what is at stake in women’s work songs. First, written testimonials and transcriptions from oral interviews show that, for many mondine, as the women workers in the rice paddies were called, their first moment of class consciousness occurred in transit. In train cars and depots, rice weeders came to understand their bodies as under reform by their migrant agricultural work. Upon arrival in the rice paddies, they gathered straw for mattresses to sleep in horse stables. Next, anger and resistance bloomed through work songs that privileged communal, turn-taking formats. It was a way to practice for alternative styles of rule. Finally, with songs like “The Union” (“La Lega”), women articulated their vision of the future: through battle hymns like this, they would raise the flags of Socialism and Communism. By swelling the union ranks, women vowed to bring about an egalitarian future in direct defiance of Fascism’s autocratic rule.